Christian Andersen, Frederiksholms Kanal 28A, 1220 Copenhagen K, +45 2537 4101, info@christianandersen.net

Images

Press release

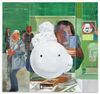

Do the following things have spirits: plants; robots; the dead; artworks; neural networks; Alexa, Siri, and the rest; financial markets, God, the atrophied bits of grey matter in your brain, quieting knowledge and memories as though they have been covered in a blanket of snow? These things exist at the borderlands of sentient life, provoking doubt. While most paintings are not alive, strictly speaking, they can contain qualities that reach beyond the technicalities of representation, towards the spirit. Not only can paint express something of the interiority of the artist who made it, the painter has a unique ability to render things with or without life. A movement of the brush, a smear of color this way or that, is the difference between something that hums with presence and something that is flat and soulless. I take these flickering apprehensions of liveliness or its absence to be a central concern of Wang Zhibo’s work, which she registers in her everyday experience, and in her studio. The moment when two fellow passengers on a train seemed as though they were plants or statues, another when a person’s face became a mask with hollow eyes, another when a wooden doll seemed to look right through her, and another when pears wrapped in paper seemed as though they were swaddled protectively, like infants, and so became, for a moment, like infants. The uncanny status of these subjects is summoned by her compositions, which reproduce the gaze between a subject and an object, and potentially the objects return of that gaze.

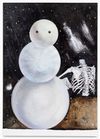

Wang paints objects in temperatures that do not seem to belong to them: fruit which has the warmth of bodies, skin with the coolness of plants. Recently, she has employed a repeated motif emblematic of crystalline, subzero coldness. Figures resembling snowmen populate her paintings, with mad, cheery coal-black eyes which stare, but which never meet your gaze: they are voids. The snowman is an everyday artwork and one that, since childhood, we are encouraged to confer life upon, adding scarves, hats and other accoutrements that bring him into the world of the living. Yet, as Wang points out, the figures in her paintings are not snowmen but figures that assemble themselves before our eyes using the snowman as a visual echo. The circular forms that make up the classical body and head of a snowman are too perfect in Wang’s paintings: they are precise, Euclidean discs containing smaller concentric circles, they are not solid, they are not made of now. What are they? Echoes, vibrations, mathematics, pulses, energies. In the same way that we might mistake a snowman for something alive, these might suggest the cool intelligences that we live with every day, that behave like friends. Formulas, algorithms, technologies, signals, forms of AI and other technologies that meet us with a friendly face yet have eyes that bore right though us, looking beyond us into eternity. Our ever-present companions.

Laura McLean-Ferris