Christian Andersen, Frederiksholms Kanal 28A, 1220 Copenhagen K, +45 2537 4101, info@christianandersen.net

Images

Press release

In the early ’80s, the German literary theorist and Marxist Gisela Dischner wrote, perhaps unaware of Asger Jorn, about the childlike imagination being the productive force of personal development. She did not yet discuss the imperative of creativity, but she did speak of a consciousness industry: of conscious decisions that appear as a way out but offer none; of activities that supposedly heal or that even catapult one out of the capitalist system, but ultimately do none of this. She does not doubt, however, that by truly giving care to one’s pleasurable, personal pursuits, there exists the possibility of questioning the value of those occupations she then calls work. Like cooking, teeth cleaning, painting.

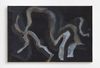

Rather than deploy conceptual severity, the three positions presented in this exhibition (Miriam’s, Edith’s, and Flora’s) each demonstrate – within an (at times, perhaps Pinterest-like) field of materiality, time, and self-reference – an ongoing engagement with the mental and material structures of production and the knowledge of things one gains. For example, the act of using a specific color until it is truly understood. Out of this practice, many possibilities present themselves. To place and read one detail against another, for example; or to attach contradictory attributes such as “abstract,” “rebellious,” and “kitsch” to the various decisions that each work contains; or to engage, all at once, in making, enforcing, and breaking the rules – all of these operations collapse ideas of a primary material experience.

That industrial work threatens to turn the producer into stone, ice, ore – or in some other form makes them dead inside – emerged as both idea and fairy tail in early Romanticism. But which (artistic or recreational) creativity can protect from a heart of stone? The latest snow queen, depressed and anxious Elsa of Disney’s “Frozen,” is a contemporary figure, not least in that she builds self-confidence through the encouragement of her sister. And indeed “sisters forever” (a slogan which has been widely disseminated on children’s backpacks and glittery stickers) earned the film positive reviews. The queen learns, through her sister, to develop trust in her own abilities. This may taste somewhat bitter, ringing of selling-out (non-romantic love); at the same time it is maybe better than any other idea Disney has developed and released into the realm of children’s imagination.

Anke Dyes

Translation by Ben Cato